Cited Loci of the Aeneid

1 Introduction

The sheer amount of data contained in JSTOR raises the question of what is the most effective way for scholars to search it. The answer to this question is inevitably going to be discipline-specific as scholars in different fields do have different strategies for retrieving bibliographic information.

For students and scholars in Classics, for example, the ability to search for articles that quote or refer to a specific text passage (or range of passages) is of essential importance. An index of cited passages, which is normally found at the end of monographs or edited volumens, serves precisely this purpose. Yet, when it comes to searching through archives of journal articles like JSTOR, full text search is often the only functionality offered. And, in many cases, it's not sufficient, or not the most effective way of retrieving bibliographic information.

Cited Loci of the Aeneid is a proof-of-concept aimed at showing how technologies that are being developed rather independently in the field of Digital Humanities, if combined together, can enable whole new ways of searching through large electronic archives. It's more a hack than it is a real project, and it is the result of an online conversation that went on for almost a year. This conversation brought together various research groups working on different yet intertwined topics: Neil Coffee, Chris Forstall, Caitlin Diddams and James Gawley who had been investigating in the Tesserae project the automatic detection of intertextual parallels within classical texts; Ron Snyder from JSTOR Labs who had been working on extraction of quotations of primary texts (e.g. Dante' Commedia, Virgil's Aeneid, etc.) and Matteo Romanello who had developed a system to capture canonical references to classical texts from the full text of journal articles.

2 Close, distant and scalable reading

The visualization of data in the Cited Loci of the Aeneid's interface was very much informed by two concepts, coming from the field of Digital Humanities: distant and scalable reading.

Distant reading, introduced by English literature scholar Franco Moretti, stands for the data-driven analysis of literary phenomena by means of quantitative methods. This idea, which has gained some momentum in recent years, has also sparked a debate among humanities scholars on whether reading literary texts is still necessary now that we can apply distant reading techniques to many of our literary corpora.

In an attempt to go beyond this dychotomy, Martin Müller has proposed the notion of scalable reading, a type of reading which moves constantly back and forth between these two perspectives on the text. Scalable reading essentially describes what happens when scholars have distant reading tools at their disposal. The patterns that emerge only when looking at a corpus of text from far force the scholars to go back and read the texts in order to understand and make sense of these patterns.

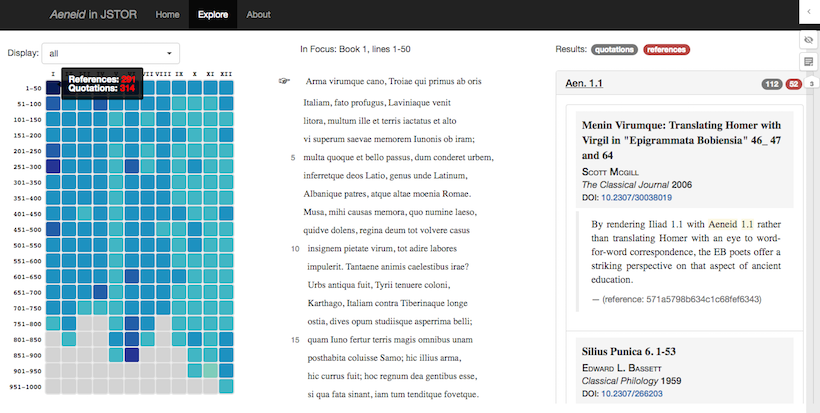

The visual index (i.e. heatmap) displayed on the left side of the interface provides a birds-eye view on the distribution of more than 11,000 quotations and roughly the same number of references across various books of the Aeneid. At a glance, the reader can detect some patterns, like for example the fact that Book 6 -- where the story of Aeneas' descent into the underworld is told -- has been quoted and referred to a great deal by scholars. The "scalable element" of the interface consists in the ability of selecting a text chunk of interest from this visual map and then examining the contexts where these quotations and references appear.

3 Behind the scenes: extracting quotations and references

On a technical level, quotations and references are extracted from JSTOR articles using two quite different approaches. Quotations are captured by means of Matchmaker, a software developed at the JSTOR Labs that employs fuzzy matching techniques to find possible quotations (i.e. reuses) of a target text -- the Aeneid in this specific case -- within a set of documents. While finding quotations requires us to identify the sequence of words from the original text that are quoted, the extraction of (canonical) references consists in identifying the piece of text that refers to an ancient work (e.g. "Virg, Aen. 6.264" refers to line 264 in Book 6 of the Virgilian poem). The references that are visualised in the Cited Loci of the Aeneid's interface were captured using a method and software developed by Matteo Romanello as part of his doctoral dissertation in digital humanities. This software is able to detect references written in a variety of languages, and following different citation styles, with a certain degree of accuracy.

4 Explore, read, annotate

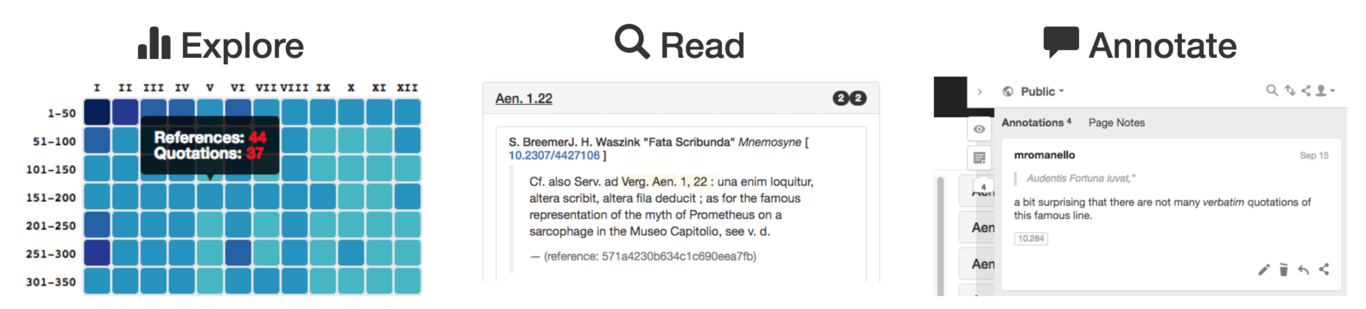

Cited Loci of the Aeneid is a proof-of-concept of a new generation of user interfaces that will allow users to access in a whole new way large archives of publications like JSTOR. The main uses it enables are: the interactive exploration of thousands of JSTOR articles; the ability of reading the part of an article that match certain search criteria without leaving/moving out of the interface; the possibility of annotating what is visually displayed, and save them to a personal space.

4.1 Explore

A visual index (heatmap), which occupies left part side of the interface, provides an overview of the frequency and distribution of extracted quotations and references. Each cell represents a chunk of the text. The darker a cell, the higher the density of quotations and references which were found for that speicific chunk of text.

4.2 Read

Matching articles from JSTOR are shown on the right-hand panel, together with the snippet of text where the quotation/reference was found and link to the article in JSTOR. The results can be filtered so as to show only article with either quotations of or references to the Virgilian text.

4.3 Annotate

Thanks to the integration with the platform hypothes.is it is possible to annotate the visualisation (either privately or publicly). This way, you can take notes while you discover new articles related to the Aeneid.

5 Current use and future developments

The tool's first use was in the context of a graduate course on Latin intertextuality taught by Neil Coffee and his collaborators Caitlin Diddams and James Gawley at the University of Buffalo in the fall semester 2016. Students rapidly understood the potential of the tool and made use of it during the course. The tool was found to be especially useful by a a group of students who sorted through a list of parallels (i.e. similar passages) between the Aeneid and Homer. In fact, it allowed them to quickly gather up scholarship around a given passage of the Aeneid, and in doing so assess whether the passage had been previously recognised as bearing some degree of similarity with passages in the Iliad and the Odyssey.

As for the future developments of this, the natural way to go seems to explore the possibility of extending the interface to cover other works of poetry beyond the Aeneid, such as e.g. the Homeric poems. However, the detection of quotations of Greek literature works constitutes a considerable challenge, as the varying quality of OCR in the JSTOR corpus prevents the Matchmaker tool from identifying existing quotations.