That Special Design Skill: The Kind of Product Designer We Hire at JSTOR Labs

At JSTOR Labs, we build experimental tools and services that expand access to education and knowledge — and that means working in ambiguity more often than not.

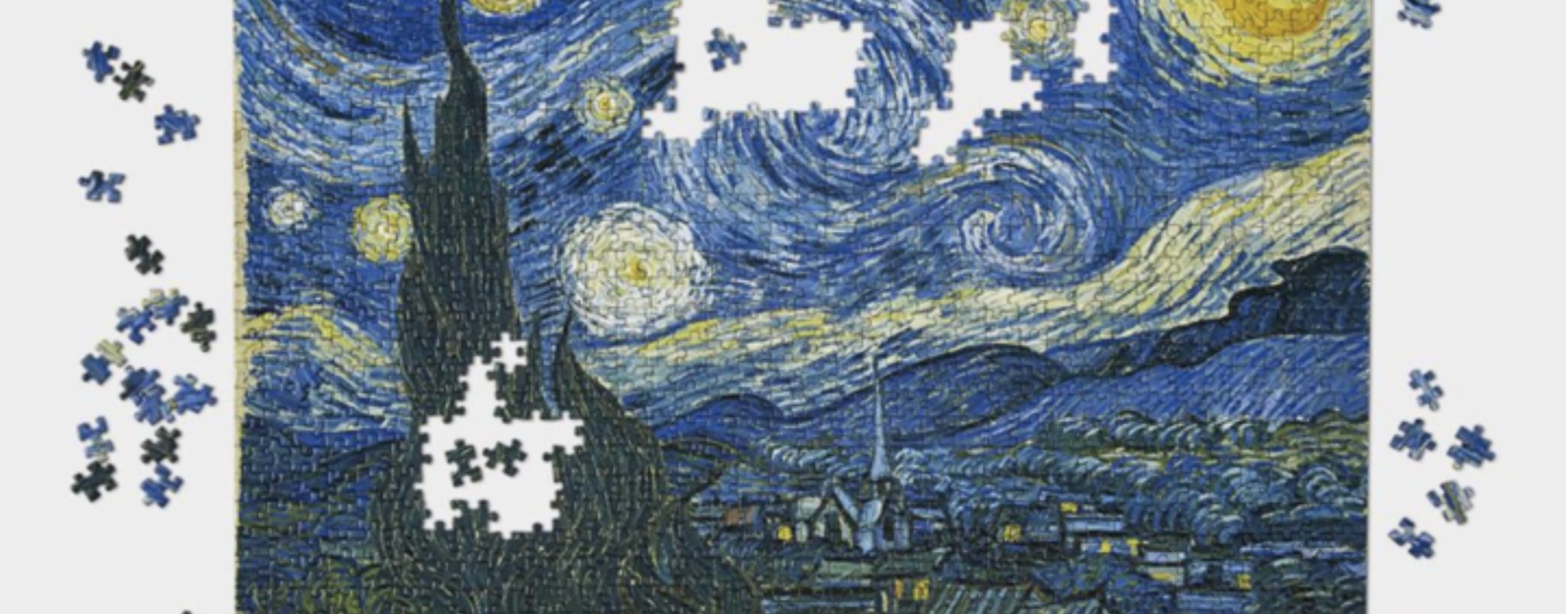

Often, UX work or product design is akin to finishing a puzzle. The picture on the box — let’s say, Starry Night — is already known. The users are known, the problems they face are relatively clear through user research, and at least a framework of a product which addresses those problems is defined. For instance, a designer might create mockups of a new feature for a product, optimize the design of a particular page to optimize important interactions, or modify the pages across a site or app holistically to improve something like accessibility or brand cohesion. Such work is important, thoughtful, creative, detailed work, but it happens within a relatively stable frame.

That’s the first kind of image I shared above.

But the kind of product designer we try to hire operates more like the second image: starting with a blank-ish canvas, a few hints, and some scattered stars. We’re still heading toward Starry Night, but we don’t have the box — and honestly, we’re not even sure if Starry Night is the right picture to be making.To be honest, I didn’t even realize it was possible to do UX or product design without a clearly defined user need — or at least a clearly defined user — until I got to JSTOR Labs. I had internalized the idea that design begins once the problem has already been named. Here, I learned that identifying the right problem is often a large part of the design work.

This work requires a different skill set: the ability to navigate ambiguity, to help define the problem, not just solve it. Our designers, as well as other designers at ITHAKA working to create new products in new spaces, are sensemakers, dot-connectors, and question-askers. They sketch, prototype, test, and explore before there’s a roadmap. They bring visual thinking into conversations where even the vocabulary isn’t settled yet.

We need people who are comfortable making progress when no one can quite say what “done” looks like — because often, we’re the ones figuring that out. Finding such people isn’t easy. But, we tend to do best hiring what I like to call broken-tooth-combed “versatilists”: people whose careers haven’t followed a straight line, but who’ve gathered skills from multiple domains and know how to move laterally when needed. These are not people who waited for someone to hand them the puzzle box and know how to make progress through messy, uncertain territory . . They’re the ones who looked at a blue wash, saw a star or two, and started building.